Gender and the authentic self

Searching for identity in all the wrong places

If one roams online trans forums as I do, one is bound to encounter euphoric posts by newly joined members expressing relief at having found their authentic self in their freshly embraced trans identities. One will encounter phrases like: “I’m finally becoming my true self,” followed by descriptions of how difficult their lives were before they “accepted” themselves as trans. The implications of these testimonials are that who they were before they “cracked their gender egg” was a false self that they needed to leave behind to become who they were always meant to be.

It’s a story familiar to me because it’s one that I also claimed as my own in the early stages of my gender transition. Having tried and failed at femininity, I concluded that I was a kind of gender outlaw that existed beyond the norms society imposed. I didn’t so much believe that I was a man, as that I was not a woman. As far as I was concerned, society was much friendlier to weird men that it was to tall weird women, and given I saw only two choices, living as a man was more appealing than the alternative. Strange as it may sound, living socially as a man allowed me to be more authentically me than the reverse.

Prior to transitioning I briefly considered living androgynously, but found that in practice this was largely impossible. So much of our lives are lived within the confines of a gender binary — friendship groups, passports, clothing aisles, intake forms, etc. We are talking more than 20 years ago now. These were the days before the category of nonbinary made it into public consciousness as a way of life and onto legal documents.

There wasn’t much about me that was feminine. Even before I transitioned, I liked to dress in jeans and button-down shirts. I wore no makeup and didn’t shave my legs. I hated wearing dresses and hated even more when strange men hit on me. Sex and sexuality scared me. I simultaneously felt ashamed of my lack of sex appeal to men and my inability to connect in meaningful ways with my female peers. All round, I felt like a fish out of water. My gender was like an ill-fitting dress.

In the early stages of my gender transition, I felt a great sense of relief. A large part of my relief came from giving myself permission to openly break the gender norms ascribed to me as a woman and that I had struggled with all my life.

Medical interventions were a vehicle for bringing my internal gender anguish into the material world so that I could do something about it. One could reasonably say that I externalized my gender problem. Externalizing is something therapists often do to help clients see their problems as separate from themselves and therefore manageable. Usually, though, externalizing one’s problems isn’t quite so literally interpreted.

Very little time passed, once I started with testosterone injections, before I started to grow facial hair, lower my voice, and blend in socially as a man. On the surface, my transition was a great success.

Below the surface, things were more complicated.

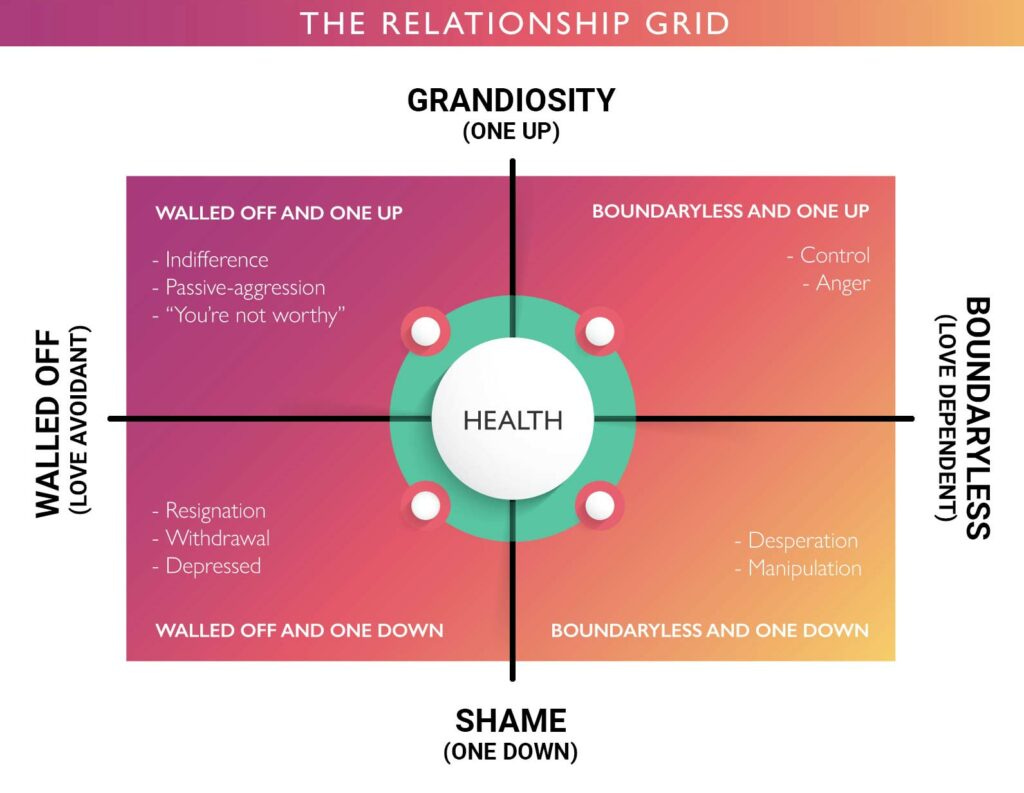

Terry Real, a marriage and family therapist and author of multiple books on relationships, distinguishes between what he calls “unbridled self-expression” and authenticity. Unbridled self-expression, he states, is the act of saying whatever is on your mind with no respect or empathy for the person you’re speaking to. Real argues that when one partner exists in a boundaryless, one-up position in relation to their romantic partner, bad things follow. Their behaviours eventually tend towards control and anger in what he calls a “love dependent” union.

I equate what Real calls boundaryless, unbridled, self-expression with entitled self-indulgence: the notion that your personal wants, impulses, perspectives and beliefs are more important than anything (or anyone) else. Real’s interest in this topic is personal — he considers himself a recovering narcissist and has written extensively on how gender conditioning prevents men and women from achieving meaningful, authentic intimacy.

Carl Rogers is another influential therapist who has thought deeply about the meaning of authenticity. Active in the early 20th century, Rogers is considered one of the founders of humanistic psychology, a branch of psychology that emphasizes human potential, the drive to personal growth and self-actualization.

Rogers believed that humans experience an innate drive to realize their full potential. The fully functional person emerges as a consequence of congruence between a person’s real self and their ideal self. Rogers theorized that a supportive environment characterized by unconditional positive regard can allow for the emergence of a self-actualized person fully in touch with their feelings, who is open to life experiences, and actively engaged in a process of ongoing growth.

For example, if a person strives towards integrity, any act that is misaligned with this value would take them further away from realizing their true self. Self-actualization, therefore is not a thing one is, but a process that relies on the person articulating and refining the values they wish to live by.

In Rogers’ work, the authentic self is not a state of being but rather a process of becoming. The actualized self emerges as a result of a constant striving to grow and improve.

Authenticity in all the wrong places

Contrast Real and Rogers’ reflections on personal and relational authenticity with group identity-based authenticities. Think of Tiktok influencers celebrating mental illnesses of various kinds as an authentic identity. Authenticity is made synonymous with diagnostic labels. Diagnostic labels become a doorway into belonging.

In these circles, authenticity is also sometimes used to justify bad behaviour. One way that claims of authenticity can be weaponized is when someone is called out for their abusive actions and their response is some version of: “that’s just the way I am”. The underlying message is that their status as a victim of social oppression justifies their abusive acts.

Certain aspects of personhood are of course difficult to alter; particularly those grounded in material reality. Things like height, eye colour, chromosomes, or age cannot be easily altered merely by wanting them to be different. But other aspects of personhood clearly are malleable. It’s why therapy works for many people. Someone who tends towards introversion, for example, can train themselves to be more extroverted. An anxious person can develop skills that diminish their susceptibility towards panic attacks. A depressed person can learn to think preemptively in ways that reduces their likelihood of relapse.

Some of the key controversies in the gender debate revolves around whether one’s sense of oneself as a man or woman or something else is a fixed, innate quality; or whether gender is instead fluid, and influenced by environment. It seems pretty obvious to me that environment plays a role. But to state this contradicts a sacred tenet used to justify gender-related medical interventions. Much of the rationale for medical gender procedures has historically relied on the premise that gender is biologically fixed, thereby requiring the body to be moulded to match the mind. Some medical experts like Dr Jack Turban, a gender-affirming psychiatrist, argue for the existence of a gender soul or a transcendent sense of gender.

But is there really evidence of an authentic gender self? And is it fixed? Research on detransitioners in particular challenge that belief. In a recent large mixed methods study of about 900 detransitioners across the US and Canada, researchers identified four different types of detransitioners: 1) those who strongly endorsed mental health-related factors and changes in self-identity as their reason for detransitioning; 2) those who endorsed changes in self-identity but remained moderately satisfied with gender-related medical treatments; 3) those who strongly endorsed discrimination and interpersonal factors as their reason for detransitioning; and 4) those who strongly endorsed discrimination factors as well as moderately endorsed healthcare access barriers as informing their choice to discontinue transition.

What can we make of this? It paints a pretty complicated picture of transitions and detransitions. It challenges the notion that gender is fixed, and also demonstrates a curious fact about humans: that we are endlessly reinventing ourselves. While debates rage on about the nature of gender identity and whether it is meaningful term to use at all, I’m more interested in how to think about living authentic lives.

Letting go of self-labeling

I didn’t really feel like I was living authentically until I stopped trying to convince myself (and everyone else) that I was a man. More importantly, I stopped worrying about being seen as a woman. Granted, I’m sufficiently medicalized now that even without any further testosterone use I will likely never again be easily recognized for what I am - a female. I can’t undo what’s done. I could pursue medical procedures to reconstruct my breasts, and start hormone replacement therapy for women. But to what end? To again have my entire existence revolve around gender?

The real freedom lies in recognizing that the identities we choose to focus on matter. And some identities are more important than others in the long run. Given a choice between prioritizing my gender identity or prioritizing my characterological identity, the latter is the one I care more about.

I don’t mind if you are cis, trans, gay, straight, or any other tribal label. I do mind if you’re respectful or not, if you are honest, trustworthy, reliable, or caring. I care if you are willing to engage in shared inquiry and dialogue. The tribal labels come and go and will continue to as cultures change. But universal values such as honesty, compassion, and respect for life endure because they matter for all of humanity.

Those are the identity characteristics I want to foster in myself. Those are the ingredients of an authentic self I look for in others.

"There wasn’t much about me that was feminine. Even before I transitioned, I liked to dress in jeans and button-down shirts. I wore no makeup and didn’t shave my legs. I hated wearing dresses and hated even more when strange men hit on me."

Same here. I was so happy when the hippies came in with hairy legs and no make-up! I did try make up, then looked at myself in the year book and went... NO. That was that.

I hated the restrictions that were placed on me from 13 on because I was a girl adolescent. I know my folks worried, but it was miserable. I loved tree climbing and rough housing and messing around all dirty. Playing cops and robbers. I was always given a hard time for coming in with torn clothes. When the other girls were trying to emulate adults, I felt so alienated. I just wanted to be a kid, a human.

Blessed be the tomboys and the hoydens! :-)